Helen J Burgess

pockets@polyrhetor.io

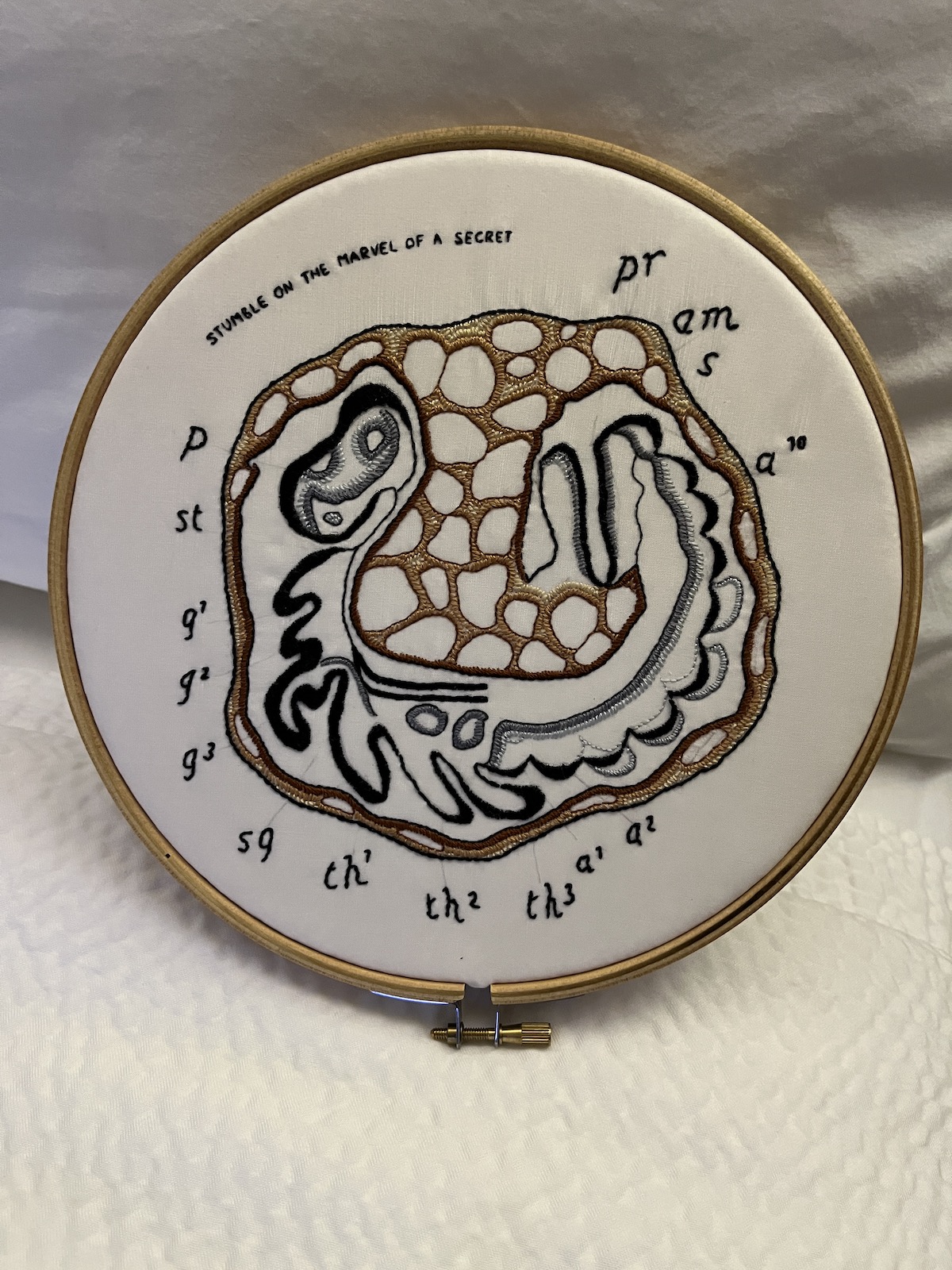

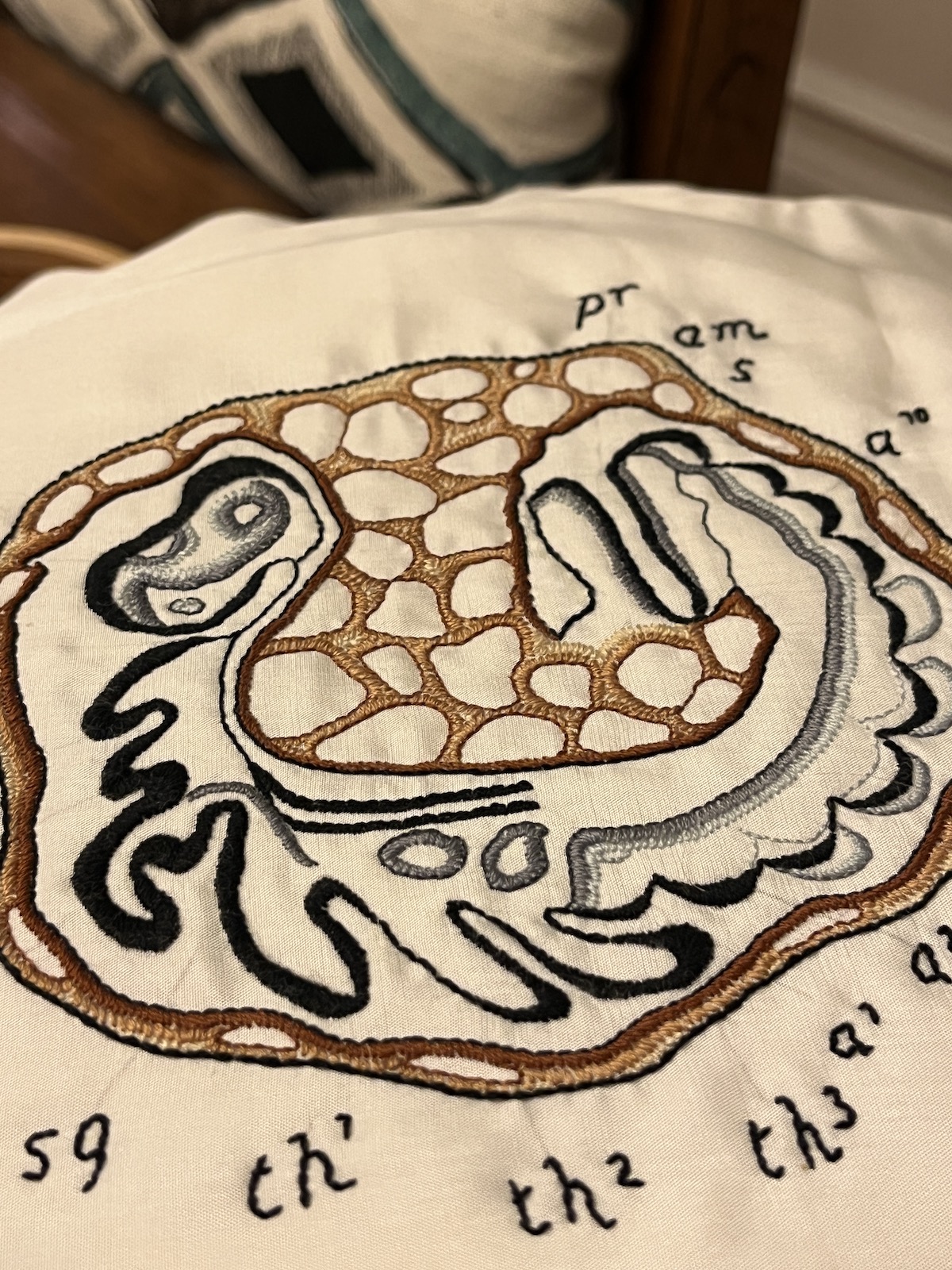

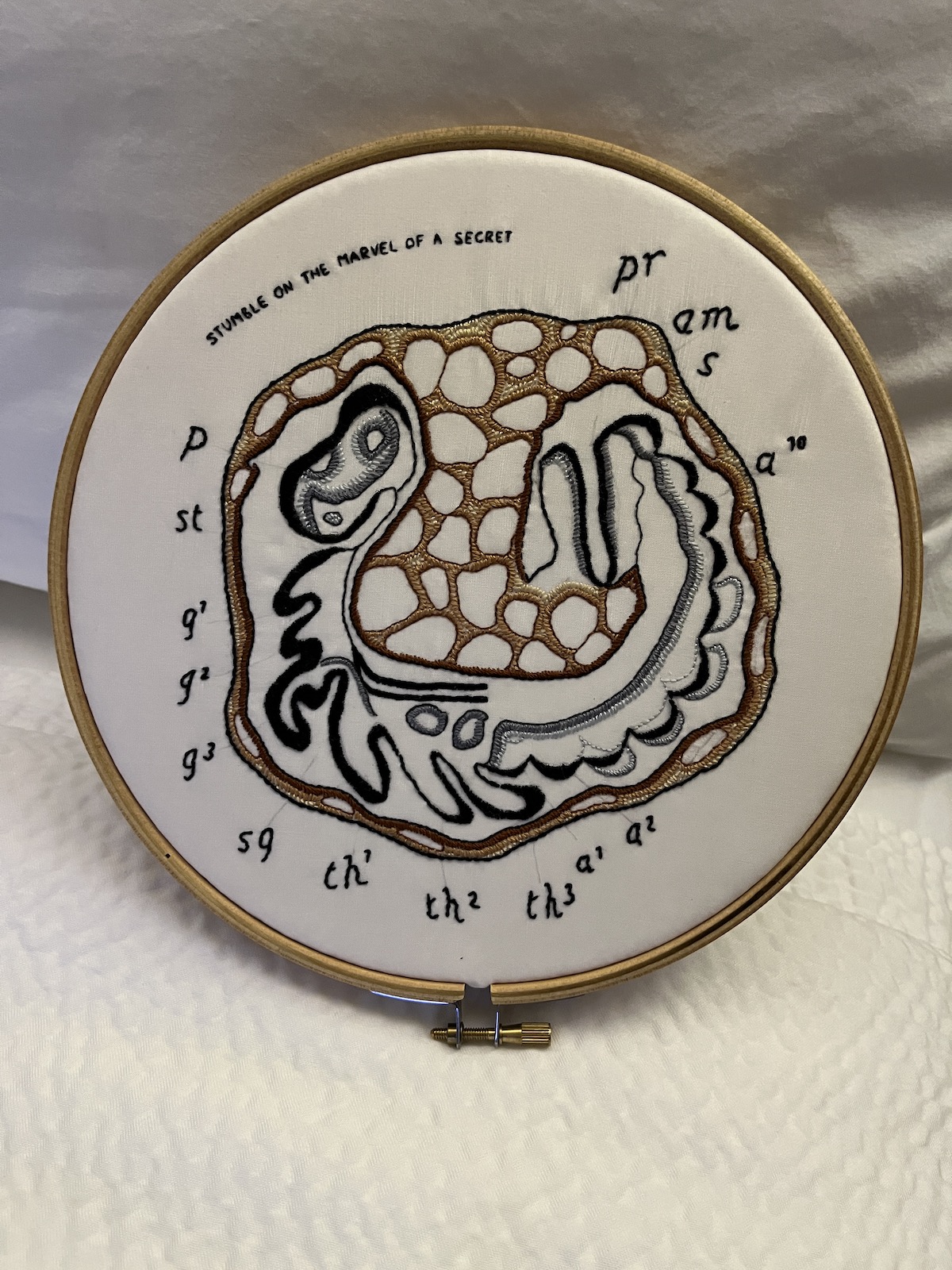

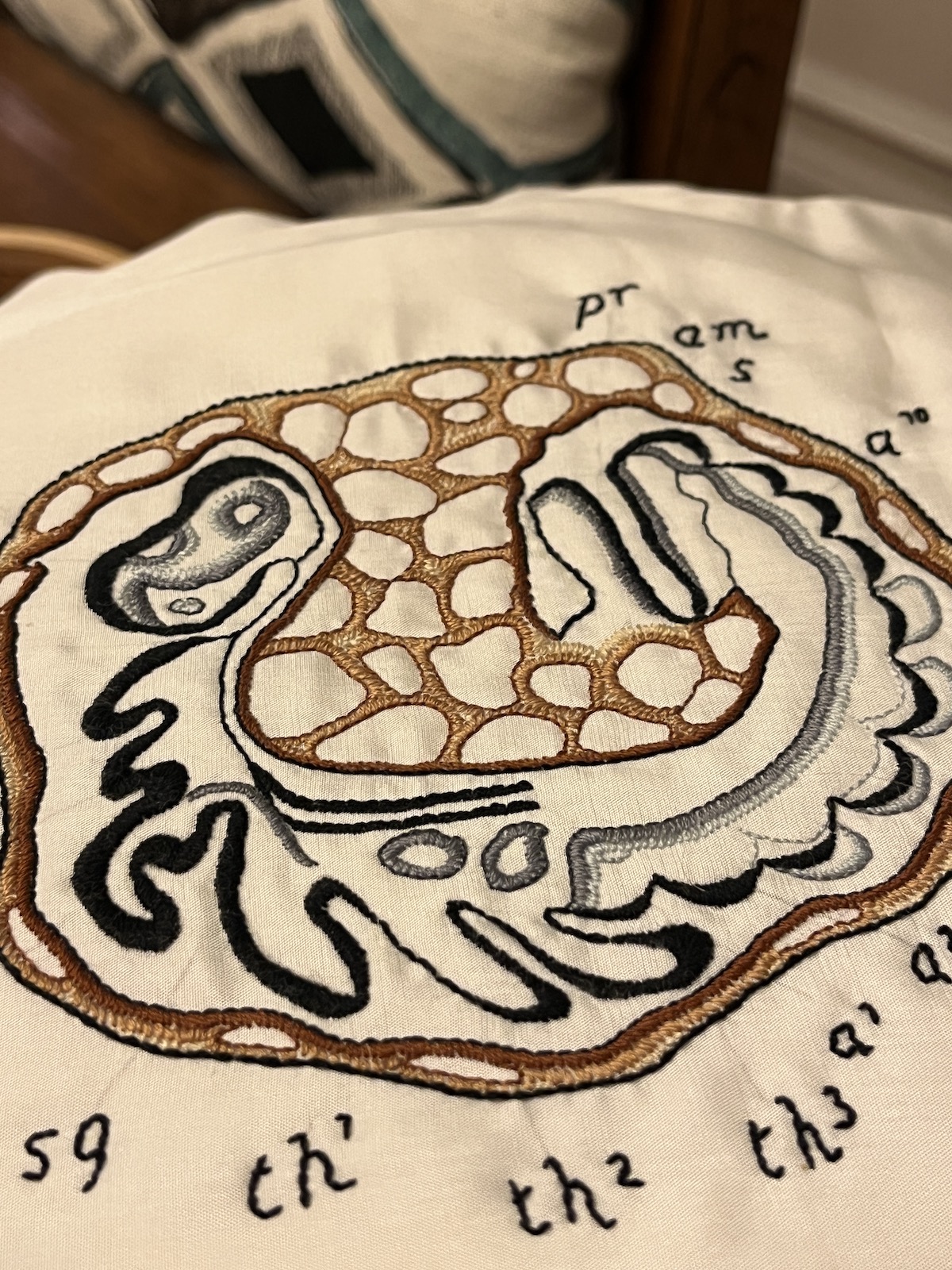

Imaginal Pockets is a textile installation that consists of four embroidered hoops, a silk pouch, and two padded silk artifacts, embroidered on one side with scientific illustrations of insect body parts and mulberry leaves, and with lace “pockets” attached on the obverse containing silk thread, lacemaking bobbins and other materials. Each is embellished with ribbons embroidered with quotes from Jacques Derrida’s “A silkworm of one’s own,” Hélène Cixous’ Veils and Lisa Robertson’s Proverbs of a She-Dandy.

The pockets are inspired by the phenomenon of “imaginal discs,” cellular clusters that lie dormant in moths and drosophila until they are activated during pupation. Each cluster forms a different part of the adult imago - wing, leg, eye, antenna - through a process of inversion, wherein they turn inside out and release cells necessary to grow the limb or sensory organ. I reimagine these cellular discs as “pockets” containing raw materials and knowledge, offering them as a generative metaphor for understanding hidden potential and transformation.

Silkworms (the primary focus of this installation) are simultaneously economic entities, art-producers, and knowledge-makers through their role as scientific model insects. They are inveterate travelers, having been dispersed across the globe for millennia as agricultural products. This migration includes dispersion of white mulberry, the silkworm’s sole food source, which has spread globally as a secondary crop and naturalized as an ‘invasive’ plant species. Silkworms themselves undergo “migration” from one body form to another during pupation, including the addition and subtraction of body parts and sensoria – a transformation humans have capitalized on via selective breeding and husbandry. For me, thus, silkworms provide a way of thinking about both the strangeness of animal life — humans do not have imaginal discs — and the familiarity we have developed with them as an agricultural and scientific companion species.

In the essay, I draw conceptual inspiration from Derrida, Cixous and Robertson’s works, which are all recast as fragmentary quotes that wander across the space of the hoops and pocket artifacts. The essay explicitly engages with textile work as a form of suspended making-and-waiting, referencing Derrida's concept of s’avoir (self-possession) and Robertson’s figure of the post-reproductive she-dandy to explore themes of autonomy and obsolescence during the process of insect-becoming. By utilizing reclaimed silk kimono linings as its primary material, Imaginal Pockets also interrogates questions of destruction and recreation in both biological and artistic processes.

Materials: deconstructed silk kimono lining, silk & cotton thread, cotton quilt batting. This diagram of a moth-in-embryo comes from The Cambridge Natural History, c.1899, in an image captioned "Embryo of a Moth (Zygaenea) on the fifth day (after Graeber)." The letters circling the embryo label the individual parts of the embryo. I've stitched the key to these parts onto a ribbon for reference. The quote is from Derrida (full line: "stumble on the secret of a marvel, the secret of this secret over there, at the infinite distance of the animal, of this little innocent member, so foreign yet so close in its incalculable distance").

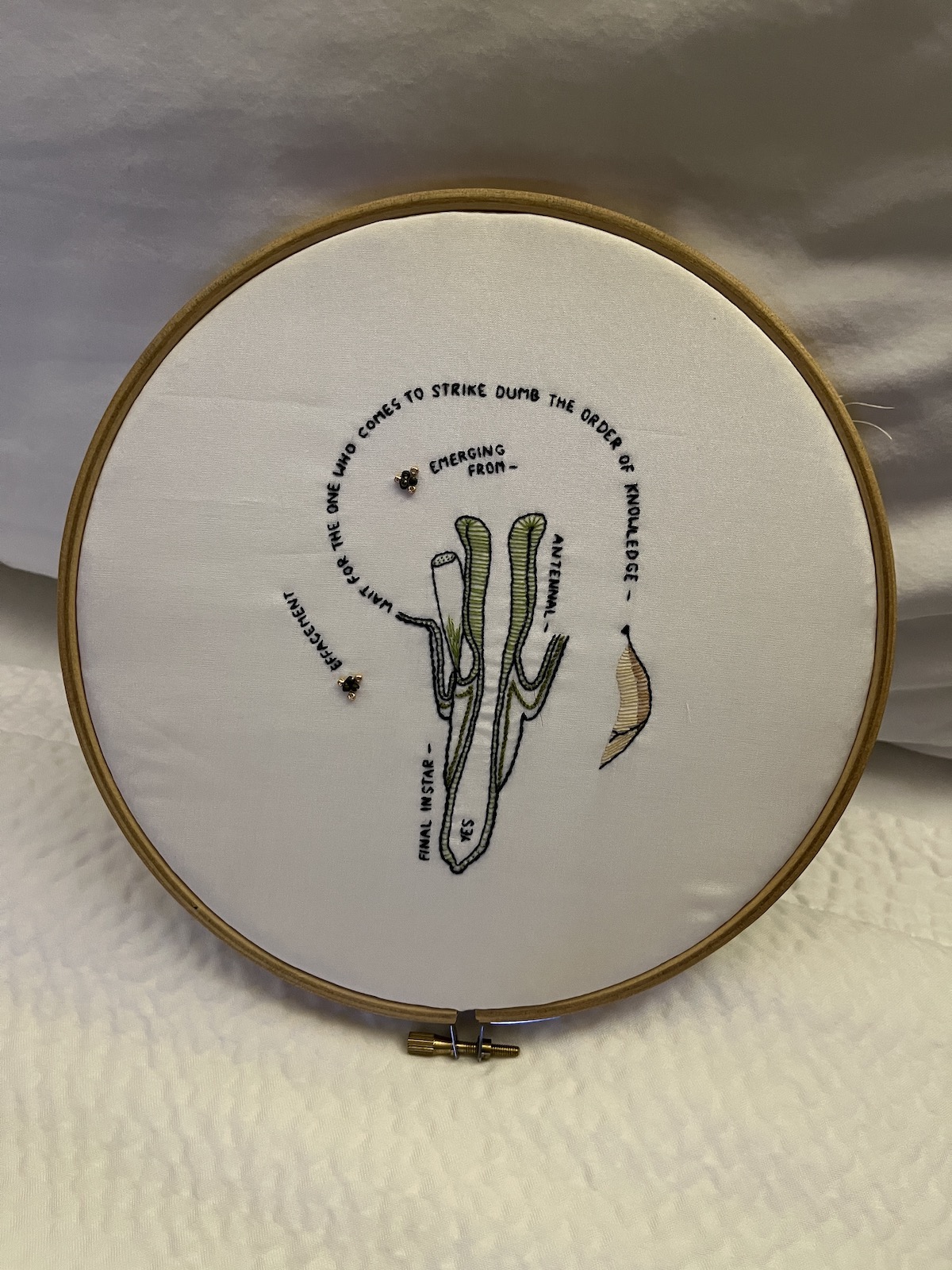

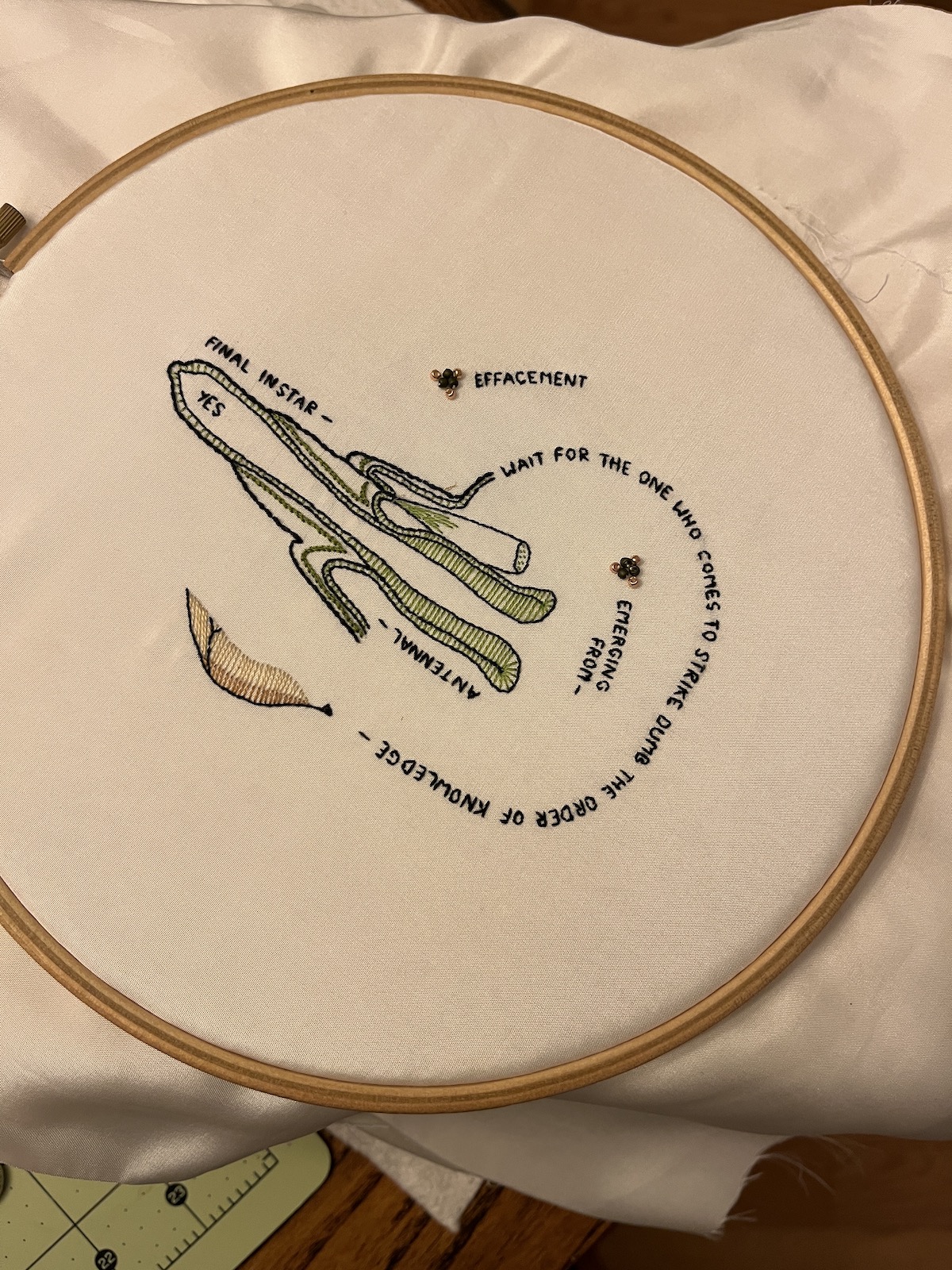

Materials: deconstructed silk kimono lining, silk & cotton thread, cotton quilt batting, glass beads. This is an antennal disc from a final-stage larval silkworm. During the process of eversion the disc (the striped green portion of the drawing) unfolds to create a feathery, pheromone sensitive and luxurious looking antenna, which is attuned to seek a mate for reproduction. The line from Derrida ("wait for the other who comes, who comes to strike dumb the order of knowledge: neither known nor unknown, too well-known but a stranger from head to foot, yet to be born") is accompanied by a quote (full quote: "emerging from effacement, she saw the world's rising") from Hélène Cixous, separated in two parts.

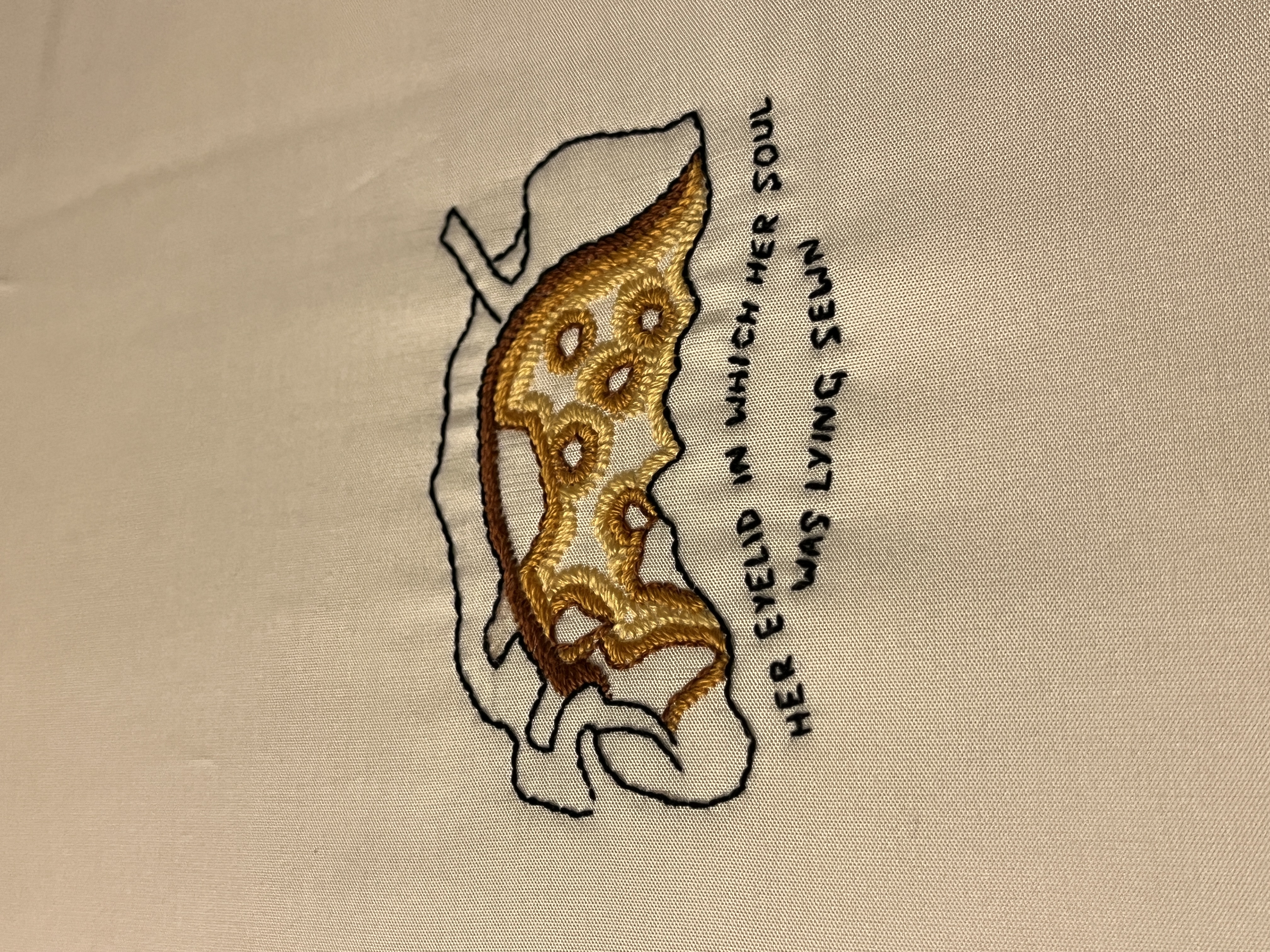

Materials: deconstructed silk kimono lining, silk & cotton thread, cricula cocoon, cotton quilt batting, glass beads. The eye disc is situated close to the antennal disc (in some insects, they are directly attached). The dark center thread in the image is the disc. This hoop includes quotes from Cixous, and a cricula silkmoth cocoon, a metallic-looking gold cocoon spun by a moth native to South Asia. Cricula silk fabrics are not well known, but the natural gold color produces particularly beautiful textiles.

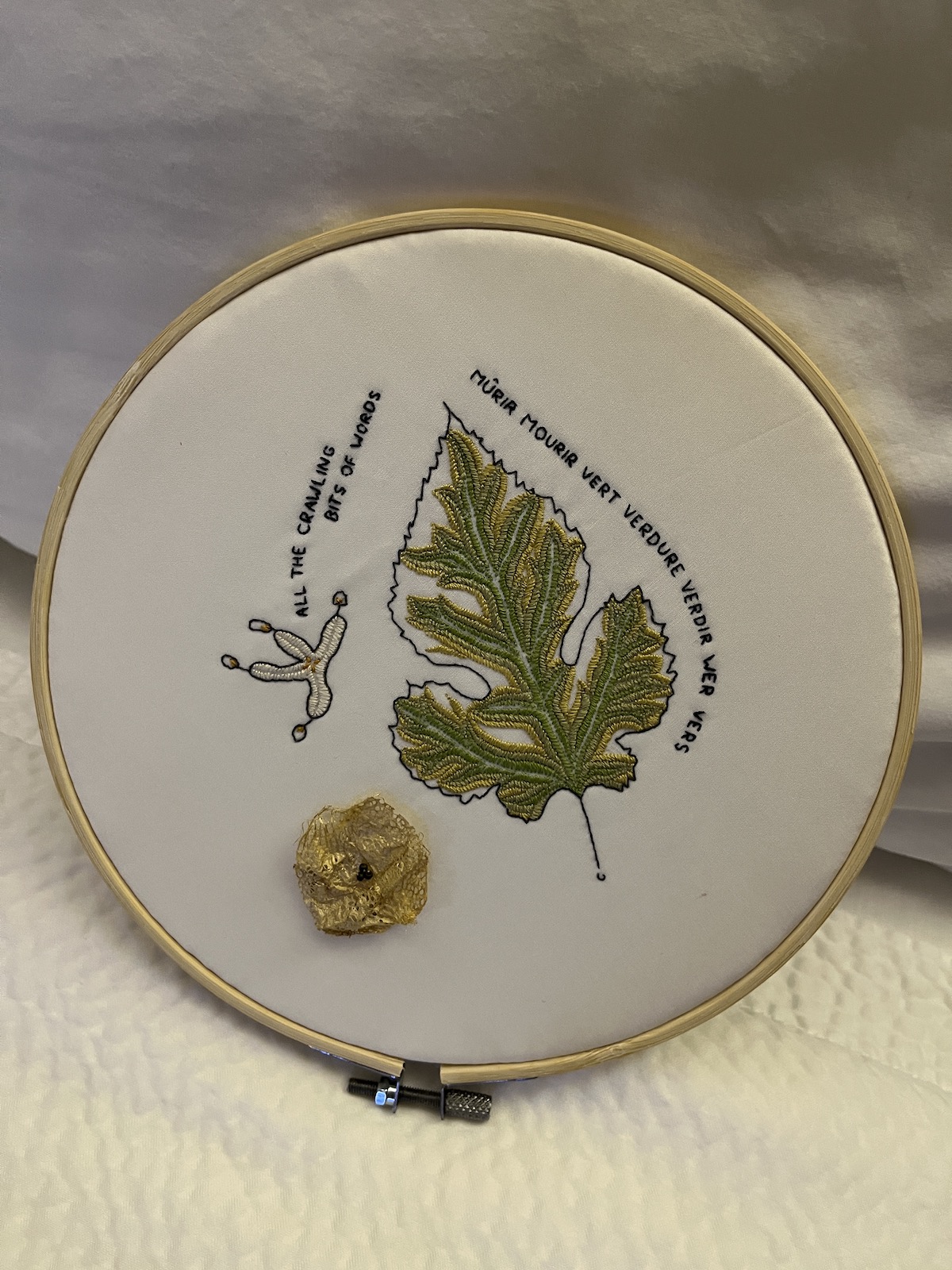

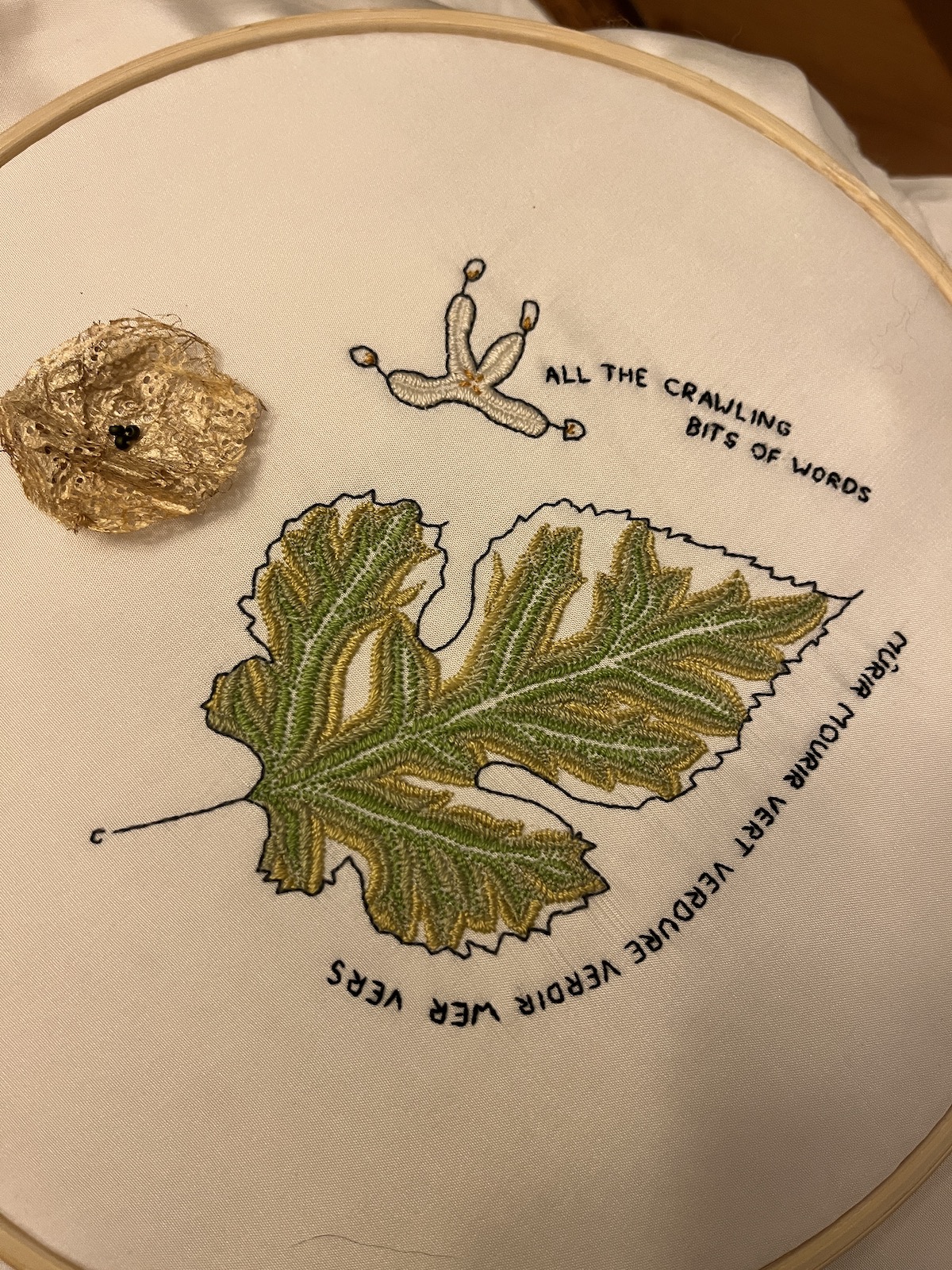

Materials: deconstructed silk kimono lining, silk & cotton thread, cricula cocoon, cotton quilt batting, glass beads. Morus alba, the white mulberry, is the exclusive food of the Bombyx mori silkworm, and they have special receptors during larval stage to find the unique scent of the leaves. White mulberry is native to China, but has spread all over the world over centuries as a companion food source essential to sericulture. Like many, my own back yard in North Carolina hosts white mulberry saplings (considered invasive), a legacy of their introduction in the 19th century in an attempt to grow a silk industry in the American South. A leaf and flower are pictured, accompanied by a cricula cocoon. The quote comes from Derrida: "The word mulberry was never far from ripening and dying [mûrir…mourir] in him … he cultivated it like a language, a phoneme, a word, a verb (green [vert] itself, and greenery [verdure], and going green [verdir], and worm [wer] and verse [vers] and glass [verre] and rod [verge] and truth [vérité], veracious or veridical [vérace ou véridique], perverse and virtue [pervers et vertu], all the crawling bits of words with ver-."

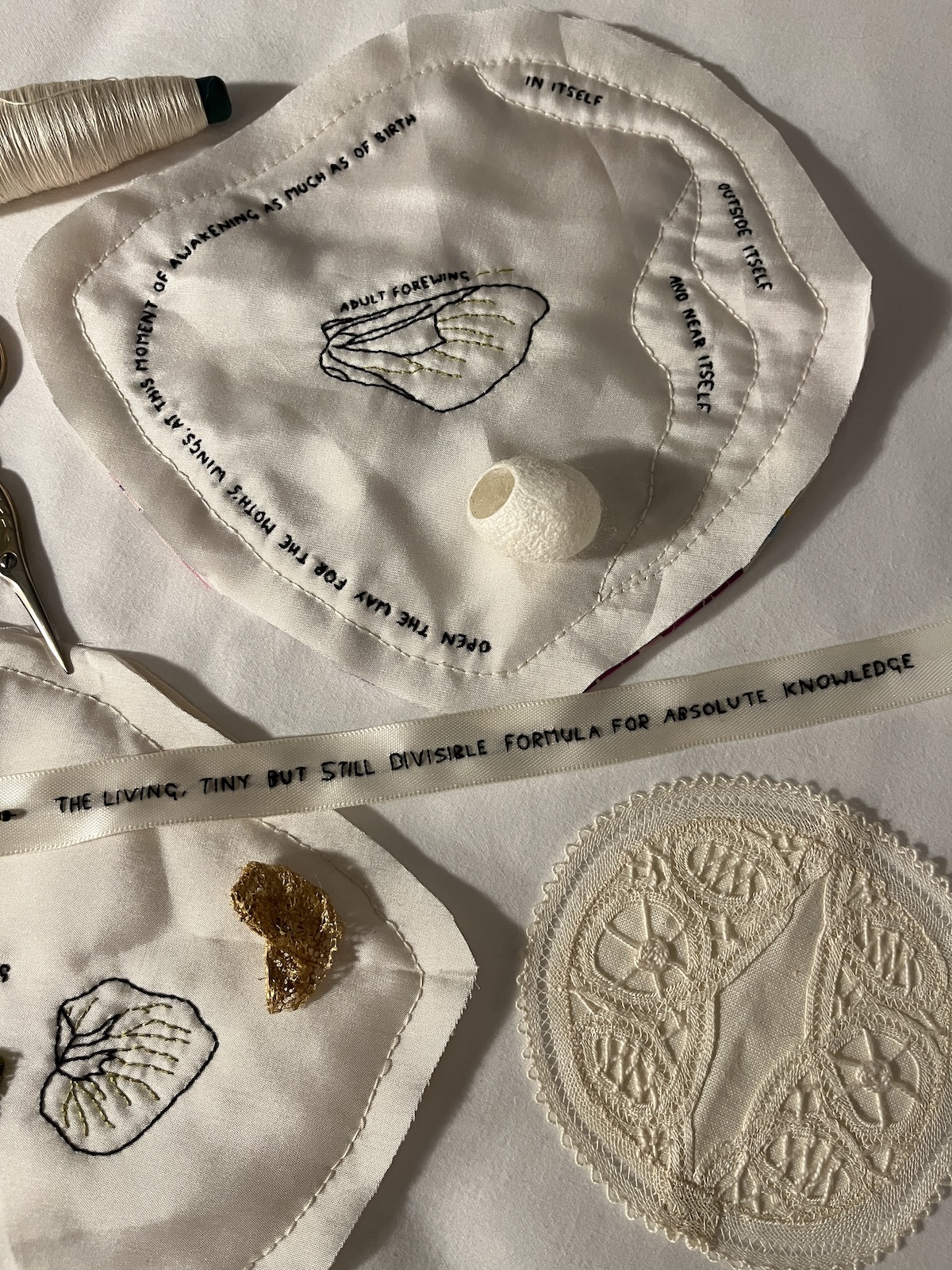

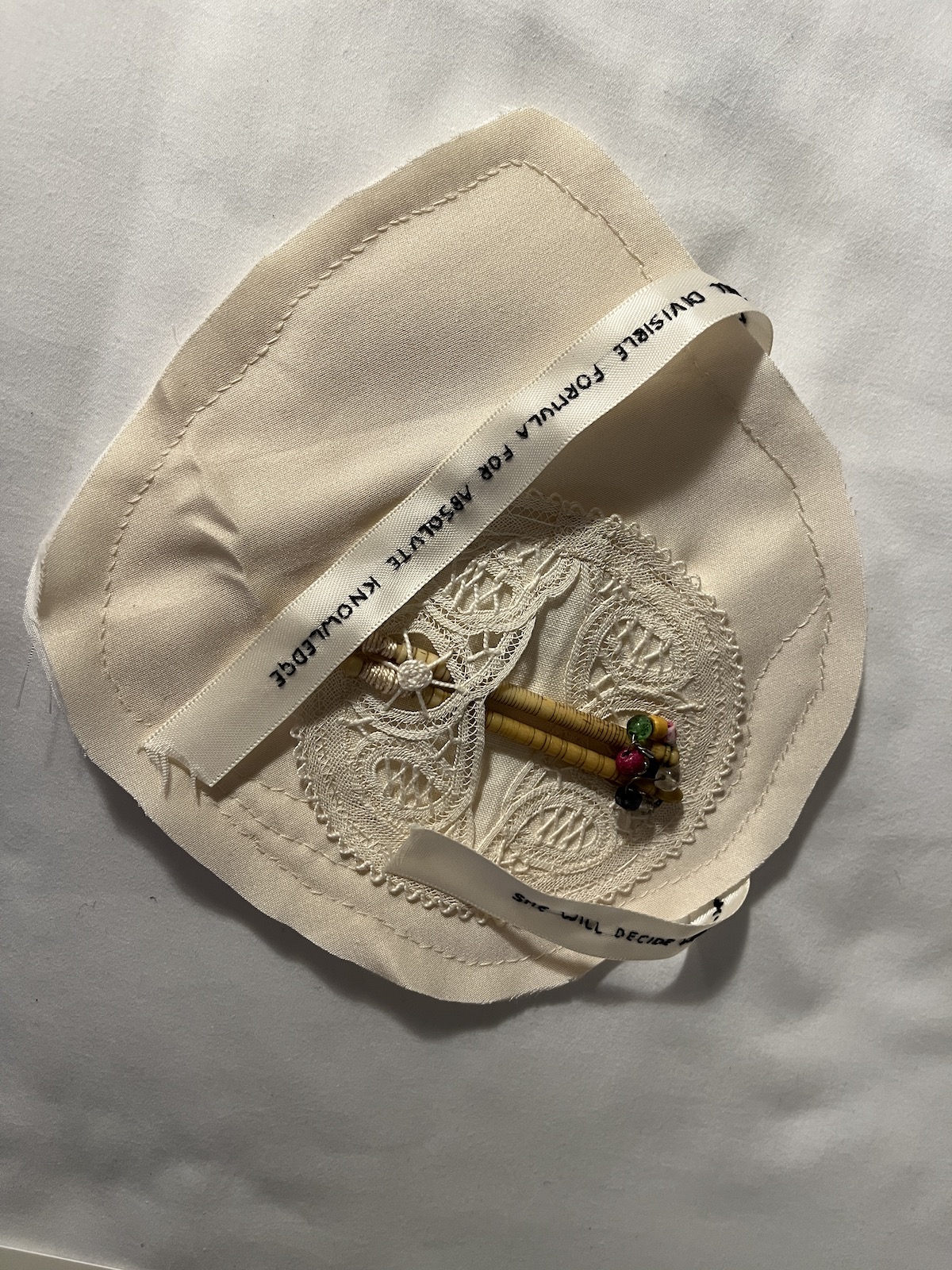

Materials: deconstructed silk kimono lining, silk & cotton thread, silk carrier rod "paper," linen Belgian lace, cotton quilt batting, satin ribbon. Usually also features bone lace bobbins and mulberry cocoons as pictured, but I accidentally left them at home. The two free-lying pockets feature the imaginal forewing and adult forewing of the silk moth. On the adult wing pocket, Derrida's full quote is "open the way for the moth's wings, at this moment of awakening as much as of birth .. the return to itself of the silkworm which lets fall its old body like a bark with holes in it" - On the latter, a ribbon is pinned embroidered with two quotes enjambed from Derrida and Lisa Robinson: "the living, tiny but still divisible formula of absolute knowledge" and "she will decide what to do with her inner wealth."

The final, small pocket features another adult forewing image, and is made from a gradient-dyed kimono sash. It is made to hold tool objects such as bobbins and scissors.

One of the most studied model insects, silkworms and their mature imago the silk moth have long been used as exemplary media for investigating the strangeness of insect life - and by extension, animal life, including our own. While research has historically focused on the optimization of silkworm bodies and processes for industrial agriculture, these insects have also become a frequent site for research into insect genetics and the foundational genome of animal life. They give us insight into tissue development and mutation; they provide us with functional schematics and cell lines. We grow them in sericultural nurseries, but also in classrooms and laboratories. As they become part of new scientific-material reconfigurations, transiting from agricultural species to genomic companion, silkworms have thus become inextricably part of our understanding of our own building blocks of life. They are, in a sense, in us, just as we, in the act of delving into their tiny bodies, are inside them.

One particularly intriguing component of insect development is the formation of what are called “imaginal discs,” cellular formations that provide the blueprints and a starter kit for growth of new body parts in the process of transforming from larval instar to final imago. While much available research in imaginal discs comes from studies of drosophila, silkworms and other lab-familiar lepidoptera are also commonly utilized for insect tissue research. These tissues are valuable to isolate since not only do they provide us with clues to insect biology and development cycles, but also a potential source of research material: “as undifferentiated cells, they can be effective sources for development of cell lines” (Lynn 143).

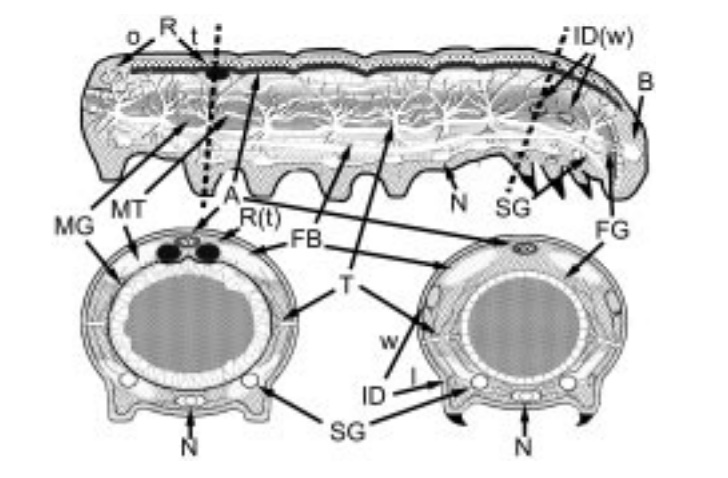

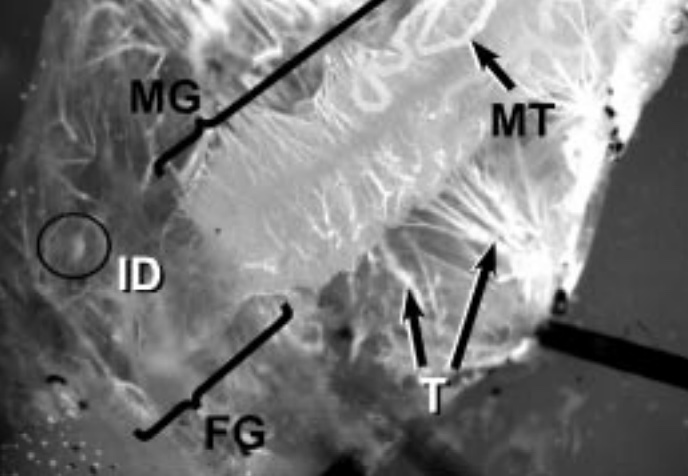

Imaginal discs are tiny. Really, really tiny. Dwight E. Lynn notes that “Their name derives from the Latin “imago” in the sense that these structures are the likeness of the adult in the larvae, but they can be so difficult to find that one might think the term derives from “imaginary.”” (143) Here’s an image, for example, of a wing disc in a Manduca sexta (tobacco hornworm) larva – the white shadow labelled ID. The cross section diagram shows fore and hindwing locations, positioned on each side of the larva near the front of the creature. (Lynn 143)

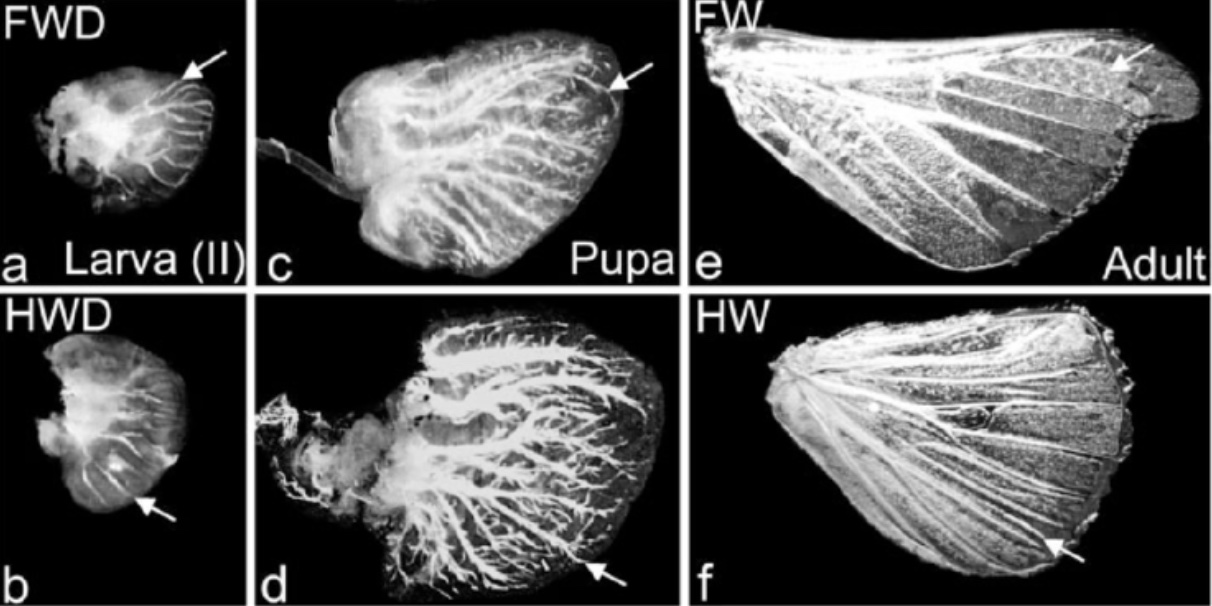

As described by Lewis Held, Imaginal discs are “flat and round like a deflated balloon” and remain so until pupation, when they evert, turn inside out (or as Held so memorably phrases, “evaginate”) and activate, working to generate the adult body of the moth. Driven by the complex regulation and expression of Hox genes, imaginal discs articulate material-technical specification documents — providing executable blueprints for wing, leg, eye, antennae. Wings form, plump out and unfurl; legs unwind from their snake-in-a-basket pose, grow joints and casings. The eye-antenna discs proliferate sensory equipment, ready for air and motion capture. In Lynne’s language, imaginal discs are “destined to become” (146); they are tissue clusters that exemplify dunamis, the energetic potential that produces change. Here's an image showing silkworm forewing and hindwing discs schematic in more detail, as they develop from larva to pupa to adult:

Manipulation of this becoming can lead to unexpected results. Hox genes, for example, determine ordering along the head/tail axis of the insect; a mutation in the antennapedia Hox gene Antp, will cause drosophila antennae and leg discs to scramble their positional instructions, leading to an ectopic pair of legs growing out where antennae should be. Conversely in silkworms, antennapedia mutation leads to “a transformation of the prothoracic legs into antennae … and a severe growth suppression of the silk glands” (Nagata 555). Mutation of the intersex (ix) gene with CRISPR/Cas-9 techniques causes sterility and mutation of external genitalia in female (but not male) adult silk moths, along with imaginal disc malformations of wing, antenna and leg, while bombyxin, an insect insulin peptide analog first discovered in silkworms, acts as an experimentally controllable growth factor for wing imaginal discs (Mizoguchi).

The language of scientific papers describing silkworms fascinates me. In addition to Lynn’s “destined to become,” the quickest of scans reveals such evocative phrases as “precocious metamorphosis” (Daimon et.al, E4226), and “fate map” (Kyoda 79). Developmental Cell journal, in an article highlight, describes the development of a drosophila wing disc as “like an origami crane forming from the folds of a paper” (i), while Lewis Held’s delightful book Imaginal Discs: The Genetic and Cellular Logic of Pattern Formation includes such language as “Models, Mysteries, Devices, and Epiphanies,” and cites Aristotle and Homer. And of course my favorite phrase, “Expression of Nubbin.” But interwoven with this language of life, becoming, precocity and growth is the tender underbelly of biological research. Lynne’s essay, consisting of detailed instructions for initiating new cell lines from lepidoptera, is affectively difficult to read, with its references to starving, immobilization, pinning and excision; what Madhuri Kango-Singh refers to elsewhere, euphemistically, as “perturbing.” Perturbation of imaginal tissue leads to highly specific developmental changes; for example this image shows how the excision of a portion of the wing imaginal disc leads to a corresponding absence of a portion of the wing once developed.

In Imaginal Pockets, I’m trying to get at the nature of imaginal discs as generative material metaphors. They exemplify the inside-out and outside-in of insect life and the larval rebirthing process, but they also call us to think about the way we imagine life to unfold: as a kind of moment-to-moment transformation from hidden potential (dunamis) to actuality (energeia). Pockets are my preferred companion in this elaboration. Pockets contain secrets. The injunction to “turn out your pockets” is an injunction to reveal what is hidden; I am reminded of medieval women’s manche sleeves, used for concealing love notes as well as prayer-books. I’ve attended many a graduate convocation when my colleagues and I have done the same with our regalia robes, secreting cellphones or books in our voluminous sleeves to furtively read when no-one’s looking (hint: someone’s always looking). Secrets, hidden treasures. Writing on the down-low. Here I reframe imaginal discs as pockets that contain strange, generative components for organism reassembly, making use of scientific illustrations of imaginal discs. Everting an imaginal pocket, like a pop-up book, reveals the growth of an inner life usually concealed by the cocoon in pupation.

In this project I’m guided by three writers: Hélène Cixous, Jacques Derrida and Lisa Robertson. Derrida’s essay “A Silkworm of One’s Own (Points of view stitched on the other veil)”, published in Oxford Literary Review and shortly thereafter in a short book coauthored with Cixoux entitled Veils, offers a meditation on, as with most of Derrida’s work, many things simultaneously: including faith, obscurity, vision, sacred prayer shawls, an epic takedown of Freud in favor of Cixous, and the complexities of savoir (knowledge) and s’avoir, which he glosses as “belonging to oneself.” Cixous, meanwhile, is similarly engaged in a meditation, on eyes, seeing, and becoming. Her experience with an eye surgery ("born with a veil in her eye" (6)) is transformed in her writing into a loving embrace of "seeing-with-the-naked-eye," while at the same time recognizing the loss of that other self, who was a member of "her own, her tribe, the myopic." Thus the transformation is both joyful and bittersweet, encompassing both "the jubilant .. 'yes, I'm here'" and "the mourning of the eye that becomes another eye."

In his essay, Derrida draws on the figure of the veil as that which separates “the holy and the holy of holies,” noting the difference between these two as a kind of crafting labor division: “Like their manner, their hands, their handwork and the place of their work: inside, within the secret for the artist or the inventor, and almost outside, at the entrance or the opening of the tent for the embroiderer, who remains on the threshold.” The silkworm, as Derrida presents her, stands in for “another unfigurable figure, beyond any holy shroud,” and her emergence from the cocoon enforces patience on us, while we “wait for the other who comes, who comes to strike dumb the order of knowledge: neither known nor unknown, too well-known but a stranger from head to foot, yet to be born.”

Derrida describes the feeling of impatient waiting, waiting for the moth to emerge, and the deathly tiredness of meaning-making, proliferating veils, such that one can do “nothing other than try to enfold them in turn and pocket them, to put the whole history of our culture, like a pocket-handkerchief, into a pocket.” His essay encompasses describes my own process all too well, much as I sometimes wish I could be more instrumental, or more disciplined, in completing a project:

You're dreaming of taking on a braid or a weave, a warp or a woof, but without being sure of the textile to come, if there is one, if any remains and without knowing if what remains to come will still deserve the name of text, especially of the text in the figure of a textile. But you insist on writing to it, doing without undoing, from afar, yes, from afar, like before life, like after life. (Veils, 24)

The ”textile to come,” in this case, has morphed over time as I’ve come to grips with both material affordances and constraints (what I have available to me), and the affordances and constraints that come from being an amateur at creative crafting, and become a pocket. I tend to be a dilettante in these matters, picking up the basics of a skill – embroidery, lacemaking, crochet, spinning – and then jumping onto the next one, like I’m running out of time. Derrida’s “dreaming” takes into account both the generative and the anxious – the need to create, coupled with the awareness that the end is coming.

obsolescence

In attempting to account for this veil between life and death, I come back again to Xu’s article on manipulation of the intersex(ix) gene. Rendered sterile by the cold clammy hands of CRISPR, these female silk moths remind me of my third touchstone, Lisa Robertson’s compelling Proverbs of a She-Dandy, in which she argues that the menopausal woman, in ceasing to participate in the project of human reproduction, is freed from her concomitant participation of capitalism as a growth model. Instead, “She is the dandiacal avant-garde. Obsolescence is embroidered in her purse. She embodies the aesthetic law of constraint (16).” The figure of the She-Dandy provides for me a comfort at this time of life. The She-dandy walks through the streets, but she is invisible now. She carries with her, instead, secret treasures: a purse, an item of clothing, that has meaning and value only to her.

Failing to reproduce the next generation of silkworms, the mutated and sterile female moth has exited the cycle of agricultural capital. For the few short days in which the silk moth survives, she will (or will not) respond to pheromones of her eager suitors. But as Robertson offers, now “She will decide what to do with her inner wealth, which is entirely autonomous” (Robertson, 22) – like Derrida’s s’avoir, she belongs to herself now. She has already herself done her part in producing the silk cocoon. Obsolescence may have been embroidered in her purse, or pocket, but her message is clear: the buck stops here.

at the end of making

As with all things, when the end is near it’s time to take stock. It would be easy, as so many do, to take from bioscientific narratives that the silkworm is fundamentally only a mechanism, a piece of lab equipment, or as Lewis Held describes, “the genetic circuitry that runs the machinery.” But as Donna Haraway argues, “we must take non-innocent responsibility for using living beings in these ways and not to talk, write, and act as if … laboratory animals were simply test systems, tools, means to brainier mammals’ ends, and commodities.” As a non-innocent talker, writer, actor, and crafter, it’s my responsibility to account for the labor of the silkworm, both as a lab animal that produces the knowledge I leverage in this project, and as the commercial animal that produces of the silk upon which (and with which) I lay my own trail.

Thus, there’s the issue of care. I’ve talked about the euphemistic use of “perturbation” in reference to manipulation and excision of larval tissue. And indeed fiber work is not without its own intentional works of violence. Exeter Book riddle 56, the “loom riddle,” characterizes the work of the loom shuttle or needle as an act of wounding, reminding me of the pins that push into laboratory larval flesh:

I saw a wooden object wounding a certain struggling creature, the wood turning; it received battle-wounds, deep gashes. Darts were woeful to that creature, and the wood skillfully bound fast. One of its feet was held fixed, the other endured affliction, leapt into the air, sometimes near the land. (trans by Megan Cavell)

My needle stabs the silk, drawing thread taut. I cut with cruel scissors, large and tiny. Silk itself is commonly produced by baking or boiling pupae in their cocoons so that they don’t damage the thread on emergence. On receiving my reclaimed silk linings, which were still in full kimono form, the first thing I did was tear them apart, ripping at the seams. I am taking apart one form to produce a new one, and doing it enthusiastically, with hopes for the future, but also regret for the lost skills that went into building these silk linings. Like imaginal discs, linings are unseen, except for momentary glimpses as a sleeve falls into view. And yet their beauty is hidden there in the careful selection of patterned fabric that will only be apprehended by maker and wearer. Linings are intimate, like the discs that produce the worm that produces the silk, in a closed loop.

Derrida asks, “Finishing with the veil is finishing with self. Is that what you're hoping for from the verdict?” His question is a truth, in one sense: that finishing with this particular piece of knowledge-making will be a kind of death (or as he calls it, “the verdict”). But as the She-dandy demonstrates, hopefully being finished is not the same as being dead. If I finish, I will at least be possessed (self-possessed) of a set of pockets, that I can secrete about myself. A little treasure, just for me.

Cavell, Megan. “Looming Danger and Dangerous Looms: Violence and Weaving in Exeter Book Riddle 56.” Leeds Studies in English 42 (2011): 29-42. University of Leeds.

Cixous, Hélène, Jacques Derrida & Geoffrey Bennington (2001). Veils. Stanford University Press.

Daimon, Takaaki, Miwa Uchiboria, Hajime Nakaoa, Hideki Sezutsub, and Tetsuro Shinoda. Knockout silkworms reveal a dispensable role for juvenile hormones in holometabolous life cycle (2015). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) 112 (31). DOI:10.1073/pnas.1506645112

Derrida, Jacques, & Geoffrey Bennington (1996). A Silkworm of One’s Own (Points of view stitched on the other veil). Oxford Literary Review, 18(1/2), 3–65. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44244481.

Developmental Cell. “In Brief.” Introduction to Tozluoǧlu et al., Planar Differential Growth Rates Initiate Precise Fold Positions in Complex Epithelia, Developmental Cell (2019), Vol. 51, Iss. 3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2019.09.009.

Haraway, Donna (1997). Modest_Witness@Second_Millenium – FemaleMan meets OncoMouse. New York: Routledge.

Held, Lewis I. Imaginal Discs: The Genetic and Cellular Logic of Pattern Formation. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kango-Singh, M., Singh, A. & Gopinathan, K.P. The wings of Bombyx mori develop from larval discs exhibiting an early differentiated state: a preliminary report. J Biosci 26, 167–177 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02703641

Kyoda, Koji & Kitano, Hiroaki. (1999). Simulation of genetic interaction for Drosophila leg formation. Pacific Symposium on Biocomputing. Pacific Symposium on Biocomputing. 77-89. 10.1142/9789814447300_0008.

Lynn, Dwight E. Lepidopteran Insect Cell Line Isolation From Insect Tissue. Baculovirus and Insect Cell Expression Protocols. Humana Press, 2007. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-59745-457-5_7.

Mizoguchi, Akira and Naoki Okamoto (2013). Insulin-like and IGF-like peptides in the silkmoth Bombyx mori: discovery, structure, secretion, and function. Front. Physiol., Volume 4.| https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2013.00217

Nagata T, Suzuki Y, Ueno K, Kokubo H, Xu X, Hui C, Hara W, Fukuta M. Developmental expression of the Bombyx Antennapedia homologue and homeotic changes in the Nc mutant. Genes Cells. 1996 Jun;1(6):555-68. DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1996.d01-260.x.

Robertson, Lisa. Proverbs of a She-Dandy (2017). Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery.

Tozluoǧlu, Melda, Maria Duda,Natalie Kirkland, Ricardo Barrientos, Jemima Burden, Jose Muñoz & Yanlan Mao. (2019). Planar Differential Growth Rates Initiate Precise Fold Positions in Complex Epithelia, fig. 1, “Characterization of Wing Imaginal Disc Morphology.” Developmental Cell. 51. 10.1016/j.devcel.2019.09.009.

Xu, Jun, Ye Yu, Kai Chen and Yongping Huang. Intersex regulates female external genital and imaginal disc development in the silkworm. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2019 May;108:1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2019.02.003. Epub 2019 Mar 1. PMID: 30831220.